How is it that seemingly sane 20th century individuals, brought up in a supposedly civilized Western country, could come to epitomize pure evil? Such, in part, is the question that the philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt attempted to answer in her well-known 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Its subtitle caused her more grief than some of its controversial content, however.

Although use of this term, “banality,” was not felicitous, she was not trying to reduce the magnitude of the Holocaust, nor to exonerate Eichmann. But it was easy for people who did not read her book, and even for many who did, to think she had. And she didn’t help herself when, in the same book, she wrote harshly about Europe’s organized Jewish communities and the Nazi-appointed “Jewish Councils” (Judenräte) for collaborating with Nazi directives, as if they had any option that didn’t require unusual courage, including a willingness to die (a choice which a few individuals did in fact make).

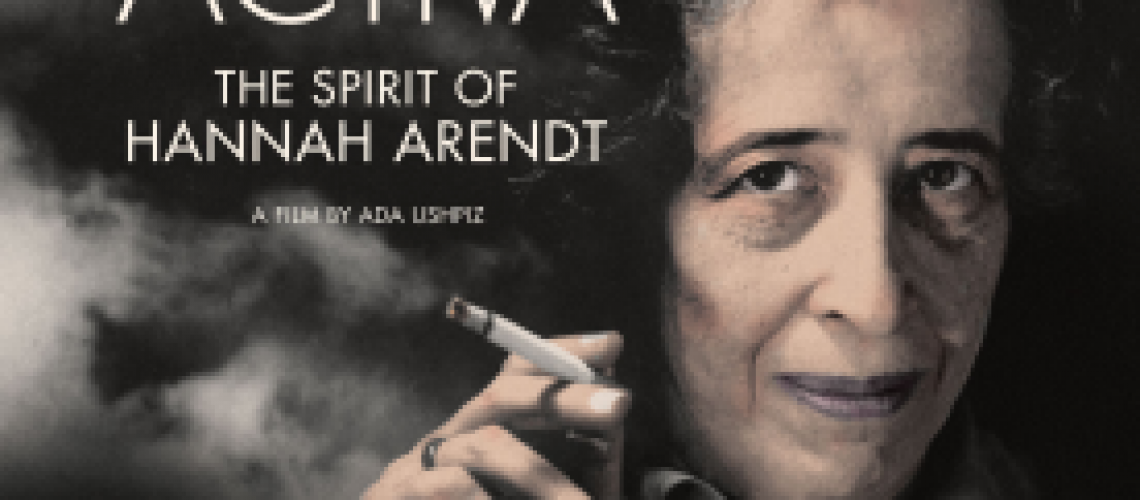

Now, having seen the new documentary, Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt, I think I understand her better. One talking-head authority prominent in the film, Richard Bernstein, a colleague of hers at The New School for Social Research, indicated that in later years, Arendt expressed regret on the way that she had written about the Jewish Councils.

In calling Adolf Eichmann “banal,” she was extrapolating from his apparent “ordinariness” — as he represented himself at his trial — to conclude that he took a central role in the Holocaust because he was “unthinking,” i.e., that he didn’t “stop and think” about what he was doing. Perhaps it’s not surprising that a lifelong professional thinker would make this rather naive assertion. Arendt was taken in by Eichmann’s act; she even came to the absurd conclusion that he wasn’t really an antisemite — as he claimed in courtroom testimony that was completely self-serving.

This was contradicted by Eichmann’s boastful tell-all statement recorded with pro-Nazi friends in South America after the war, and first revealed in 2011 by the German weekly Der Spiegel. As indicated in a Haaretz news article at the time, Eichmann extolled his role in carrying out the Holocaust and exulted in the mass extermination of Jews, even regretting that he couldn’t finish his genocidal task.

Vita Activa is a more factually satisfying film than the 2013 biopic, Hannah Arendt, which — although artfully done and enjoyable as a cinematic experience — did not confront the shortcomings in her ideas. Instead, filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta and her co-screenwriter Pamela Katz did what apparently served them best for a dramatic feature, portraying Arendt as heroic and intellectually spot-on.

What bothered me more, however, was in how von Trotta and Katz made her out to be an adversary of Zionism, rather than as someone who had spent a decade within the movement and only became critical after the World Zionist Organization adopted the Biltmore Program in May 1942; this included the demand for a “Jewish Commonwealth in Palestine,” instead of the bi-national state or federation that she had preferred. But she was a critic rather than hater of Israel.

Vita Activa did not really examine her complicated relationship with Zionism either, but it was somewhat less tendentious on this point. It included clips from West German television interviews, but not what I saw at an NYU conference in December 2006 (commemorating the centennial of Arendt’s birth). While in exile in Paris in the 1930s, Arendt had worked for Youth Aliyah. As I had put it in Tikkun in April 2011, describing that TV clip: “Smiling through a thick haze of cigarette smoke, she characterized her job of getting young German and Polish Jews to Palestine as the single most satisfying work she had ever done.”

What we do see are two or three short segments with the crusading anti-Zionist philosopher Judith Butler — basically regarding Arendt’s ideas on totalitarianism, human rights and political engagement. Still, Butler can’t resist taking a swipe at Zionism; I vaguely recall her suggesting how nationalism can lead to “genocide” — unassailable as a general proposition, but also an unmistakeable barb at Israel, given its sequence in the film, in proximity to video footage of Israeli soldiers and Arab refugees in 1948.

This film implies a clear connection between our own time’s massive refugee crisis and Arendt’s time, when she was a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. The closed doors of the West, then, were much more hermetically sealed than today. Her status in France was not legal, and she was detained in a French internment camp in 1940; somehow, she managed to escape before the Gestapo took command. Vita Activa quotes her on the desperate plight of Jewish refugees, rendered “rightless” because of their statelessness.

Such a thinker would be sympathetic to the establishment of a state granting vital rights to these Jews. She would also care about the rights taken from Palestinian Arabs made stateless by Israel; but if she or anyone else looked at this matter fairly, they would also note that a peaceful resolution displacing no one was on offer in the UN partition resolution of 1947, unanimously and violently rejected by the Arab side. And it’s only Jordan, among all the Arab countries, that has granted citizenship rights to Palestinian refugees.