Every child hears the Stone Soup story: There was no food to share in a war torn, poor town. None at all. Then a hungry and clever soldier filled a kettle with water and a few large stones and offered to make “stone soup”. He did not ask for much, just a little flavoring for his soup. Remarkably, as villagers found an onion here and a clove of garlic there and a wilted carrot forgotten in a root cellar, a nutritious meal miraculously appeared. Even a kindergartener cannot miss the message that by working together and by sharing, people are able to make something good from nothing, or almost nothing.

The Israeli Social Protest Movement, which this winter seems as long ago as Woodstock, has its heirs in the makings of a stone soup.

The tents are gone. The signs have been taken down. Many would say that the there is nothing to show for the weeks of protest in the summer of 2011, for all the cries of “Ha Am Doresh Tzedek Hevrati” (The People Demand Social Justice), for all the thousands who set up tents in the parks and the hundreds of thousands who marched in the streets and all the millions who stayed home but who hoped for a more humane economic system. Nothing.

When Ameinu was touring Israel in early January, the election campaign was in full swing and the posters covering the country emphasized security, peace, the need to keep all of the Land of Israel for the Jews. There was no mention of the price of cottage cheese or even the need to break up the oligarchies that put a basic food out of the reach of ordinary people. The country was covered in election posters, on the walls of buildings, hanging from private balconies and on the back of every bus. The only topic seemed to be foreign policy and the settlements. Likud –Yisrael Beitanu, with a photo of Bibi, declares “A strong Prime Minister. A Strong Israel.” The far right Jewish Home funded by the seemingly unlimited personal resources of its head of list, Naftali Bennett, distilled its inchoate proposal to annex Area C of the West Bank down to the slogan “This is Your Home.” Meanwhile, Tzipi Livni, who failed to form a government despite winning a plurality last time, formed a new party of egotists and warned “Likud and Bibi: Disaster. Tzipi: Peace. ” It seemed that the Ultra Orthodox Sephardic party spoke the truth with its posters declaring “Only Shas Cares for the Weak.”

Here and there were a few voices of the society protest movement among the candidates for Knesset. This was especially true for the Labor Party, which for complicated reasons is on the short end of the public campaign financing stick and therefore had almost no huge campaign posters of its own blanketing the country. A few of the social protest movement’s leaders were on the lists of candidates and two, Stav Shaffir and Itzik Shmuli were placed high enough on the Labor list to be virtually guaranteed seats as a Knesset Members. (results were not yet in when this was written.) Arguably Sheli Yachimovich, the head of the Labor Party, a TV Journalist long associated with economic welfare issues, was elected to head her party on the wave of the Social Protest Movement’s enthusiasm.

But, after the action in Gaza and renewed talk of the Iranian nuclear threat, social issues seem so “last year.” Early predictions that the Center Left Labor party might gain a plurality and a chance to form the new government receded into the mist and it seems that the new government will be the most right wing, most hard-line, ever.

So what is left of the social protests, besides a few candidates who will sit in the opposition? Actually, there are glimmers of hope that the summer of 2011 has actually made changes in Israel, not in the government but in the people.

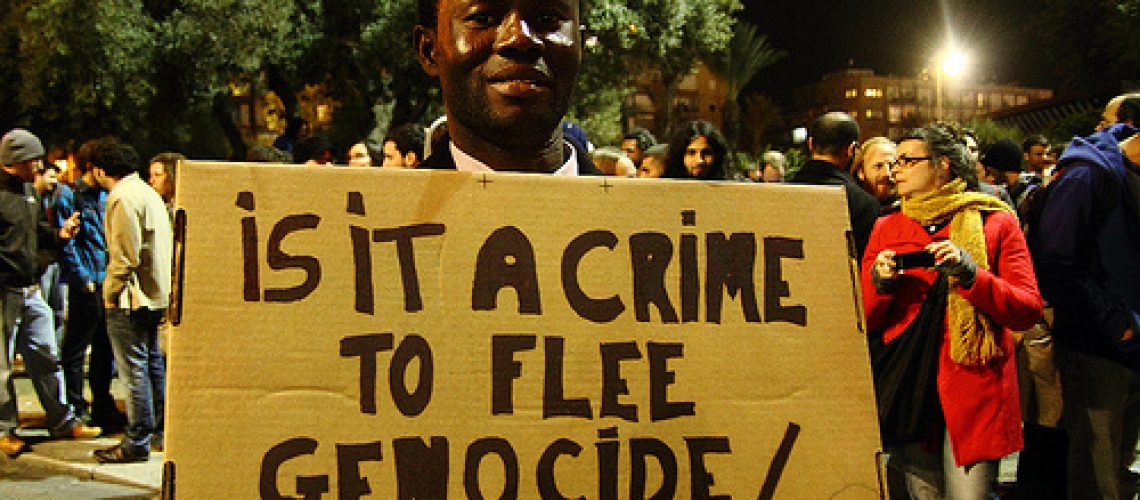

One glimmer is “Marak Levinsky”, literally “Levinsky Soup”. The name comes from Levinsky Park, a park that is no longer really a park but rather the government’s chosen dumping ground for the people alternatively called African Asylum Seekers (the PC name) or Sudanese/Somali/Eritrean Infiltrators (the government’s name) or refugees (a name used by those who look at the people’s homeless, nation-less lives and do not understand the international bureaucracy that allows some people like these to be called “refugees”, but does not apply the name to these specific people in these specific circumstances) . Until recently, the fate of these people who escaped arrest for political “crimes” (or simply starvation) at home, who walked across Africa, who faced bullets and beatings in Egypt, who braved death from thirst and torture at the hand of extortionist kidnappers in Sinai, was to be forced on to buses as soon as they crossed into Israel, taken to Tel Aviv and dumped in Levinsky Park. (Now they have much more difficulty reaching Israel due to the new security fence on the Egyptian border and if they do make it, they are bussed to a new prison camp in the Negev.)

Not only are there a couple hundred men living in the park, but several thousands (plus some women and children) are also crammed into the crumbling, low rent buildings nearby in the area surrounding the Tel Aviv bus station. These people come into Israel from somewhere so much worse that sleeping out in the cold rain of a Tel Aviv winter with slim prospects of earning cash from casual, illegal jobs is worth risking their lives. And who has embraced these foreigners? Almost no one. MK Miri Regev called them “a cancer” and then had to apologize to cancer patients. Despite statistics to the contrary, they are widely regarded as thieves and rapists, the scum of the Earth. A few leftist organizations champion their human rights. But no one cares for their most basic need. No one, except a new sort of loosely organized group of former social protestors. Organized by facebook and twitter, without NGO status, without any budget, somehow Marak Levinsky—an Israeli “Stone Soup” Soup Kitchen—is feeding the people living in and around Park Levinsky.

Not just the food but the “facilities” of Marak Levinsky are as improvisational as a stone Soup. Somewhere, someone obtained an old ZIM shipping container, which sits on the street (thanks to a currently tolerant city administration that could change its mind), and houses a few clothing storage shelves, that are emptied nearly as soon as donations come in to fill them.. There is a facebook page to announce needs. And a couple of cell phone numbers. Two very large tarps made out of a collection of smaller tarps are the basic shelter over 60 old army cots softened by 60 old thin foam mattresses with ripping cloth covers plus less than 60 blankets to go around. This ragtag facility is run by an army of volunteers, veterans of the social protest movements–people originally who came to the streets to tell the government that they did not have enough to pay their own rent, to buy their own food, to have another child, to afford university. Now those who were complaining about how little they have are helping those with absolutely nothing.

At Marak Levinsky, the need for hats and gloves, big warm coats, large sweaters, and pants to cover long, long legs—much longer than those of the average Israeli—is seemingly insatiable. These are big men, men who have walked across deserts to safety, men who have never needed coats. And now if they are lucky enough to receive one, they are often squeezed in cast-off coats that don’t reach their wrists.

These are strong men in their prime, men who are desperate to work, but they are not allowed. They have no status and so they cannot be legally employed. All they can hope for is casual jobs, usually day by day. There are plenty of foreign workers in Israel—about 300,000 of them, with more are imported annually. These men could take those jobs, but the Israeli government prefers workers imported from Thailand, the Philippines and Romania, workers who can theoretically be sent home when their permits expire.

These asylum seekers have come to a country that has no process for evaluating their eligibility for asylum. It classifies most of them as enemy infiltrators because they come from countries officially at war with Israel. The government of Israel wants to discourage these people as much as possible. It proves no services.

But these people have come to a country where some people can look at these huge men with midnight black skin and see their own beloved tiny Polish bubbeh who survived the Shoah because a local peasant hid her in a basement and fed her scraps. Asked why they do this, the “secular” volunteers at Marak Levinsky say they do this because they must, because their Judaism compels them to do it. In the heart of secular Tel Aviv, thousands of former protestors have found a connection back to their own Judaism through helping these African migrants.

The volunteers, empowered by the social protest movement, successfully petitioned the city to keep the park toilet facility open until 11 PM, rather than locking it at 6 PM. Though the park lacks even the most rudimentary facilities humans need—including no toilets for 9 hours a day, no showers, no real shelter from the cold or from Tel Aviv’s torrential rains—it is litter free and there is no stench of urine or feces. At night, 60 men sleep on cots beneath the two large tarps. But on a stormy night those with beds welcome those who usually sleep on the benches, playground slides and on the bare ground so that 100 or even 150 squeeze under the tarps. As one of the organizers at Marak Levinsky told me, “Africans are very good at sharing and they are very generous with the little they have.”

Marak Levinsky feeds hundreds of the neediest people in Tel Aviv twice a day. The 200 or so who live in the park, and some who are “luck” enough to sleep in a room with 20 or more other people somewhere near by. And the drug addicts in the surrounding community. And others who are just too poor to feed themselves. They come with bowls and pots to take the soup or pasta. Every day, twice a day. The hungry people come and somehow, out of nothing, the soup will be there.

There is no formal structure to Marak Levinsky. No NGO. There is only a network of facebook friends and cell phone connections and an artist named Yigal Shtayim who bargained with his wife to give up art for one year so that he could repay the world for saving his German grandparents. Yigal’s year as the hub of the Marak Levinsky wheel is almost up. Who will step up next? No doubt another social protestor. Just as people come by and drop off day old bread and pasta everyday, just as they donate vegetables too wilted for the grocery stores. And so a meal comes together. Day after day, the volunteers at Marak Levinsky make stone soup. A new organizer for this daily miracle in the park will somehow have to appear so that Yigal can go back to supporting his own family.

There is no guarantee it will happen, except that the need is so acute, someone will have to step forward.

Of course you want to know how you can help. But there is no way to send Marak Levinsky money. If you tell them you will be visiting Israel and want to see their miracle, they will ask you to bring an extra toothbrush, some toothpaste and a bar of soap. And a big old warm sweater too, if you have the room. And when you visit, you will also leave a bit of your heart.

The author, along with the a group of Ameinu members, visited Marak Levinsky while participating in the Ameinu “Journey” January 1-6, 2012.

To read more of Judy Gelman’s reflections on the Ameinu Breakthrough Journey click here

369 Responses